Shortage of affordable housing is real

Entities working together on several fronts to address issue

ALAMOSA — The shortage of affordable housing in Alamosa has resulted in a crisis that is ravaging the lives of hundreds of individuals and families with children, exacerbating significant social issues with effects rippling throughout the community and putting additional pressures on services that are already strained. The situation is not unique to Alamosa, but, in response, the City of Alamosa — like more than 50% of other municipalities in Colorado — is venturing into areas that, five years ago, would have been unthinkable.

To most people, the term “affordable housing” is synonymous with “low income” and, for that reason, is misleading. According to Deacon Aspinwall, one of the city’s housing gurus, “Affordable housing is housing that does not take more than 30% of a household’s income before taxes.”

As an example, Aspinwall sites a nurse living in Alamosa earning $55,000 per year. Affordable housing for the nurse would top out at $1,375 per month, including utilities plus rent or mortgage.

In comparison, a retail associate with a 4-person household in Alamosa typically has a gross household income of $25,525. Translated, the most that family of four can pay for rent that is affordable is $638 per month.

After both have paid for housing, the difference between the 70% of that nurse’s $55,000 paycheck and that retail associate’s $25,525 paycheck is the difference between night and day or — more appropriately — between those who can make it from one month to the next and those who cannot.

The financial pressures are made even worse by where the nurse and retail associate are living. In this scenario, both are living in Alamosa where, according to the 2020 census, one out of every five people lives in poverty and the median income is half what it is in other parts of the state.

When it comes to a shortage of housing that people can afford, the bottom line is right there in the numbers. The need for less expensive housing is substantially greater among the people who make up the greater part of the population and who also need it the most.

The result in a city where a significant percentage of the workforce is earning low wages is predictable. According to a housing assessment commissioned by the city in 2020, half of renters and one third of homeowners are paying more than 30% of their income for a place to live, leaving less money for other essentials in life.

The shortage is very real

As has been reported, that 2020 assessment revealed that more than 500 houses needed to be built in Alamosa to meet the demand. Last Sunday, the Valley Courier went searching to see how many apartments were available for rent. After searching online, looking in the newspaper and driving through neighborhoods, a total of nine apartments for — out of the entire city — could be found.

Among those nine apartments, the least expensive ranged in price from $525 to $700 per month for a 1 bedroom, 1 bath apartment with 375 square feet. On the upper end, a 3 bedroom, 1 bath apartment with 1,125 square feet could be rented for $1,500.

By Tuesday, only six apartments were still for rent, with the least expensive properties already gone.

The shortage has resulted in landlords being able to increase their rents substantially, knowing the market will be there to meet the higher price.

“Rent has gone up 30%, 40%, even 50% over the past year,” says Dawn Melgares, executive director of San Luis Valley Housing Coalition. “We have one client who was paying $750 and, overnight, their rent was increased to $1,500. It doubled, with no warning.”

Few families can afford that kind of increase and still stay in their apartments, leaving no option but to look for a new place to live. But with skyrocketing rents plus the typical first and last month security deposits, there are no options on the market. Even if an apartment can be found, many landlords require first month’s rent plus first and last month’s for a security deposit. And among those who can scrape the money together upfront, qualifying to rent has become increasingly more difficult.

“This significant shortage means that landlords can now cherry pick those who have solid work histories and no criminal records,” says Heather Brooks, city manager.

How big is the problem

Just like affordable housing is often synonymous with low income, a housing shortage usually equates with homelessness, which is clearly related to a shortage of housing.

Despite the homeless community being relatively transient, the numbers of people who are homeless in Alamosa are relatively easy to track because they are served by La Puente, and La Puente keeps records on the clients they serve.

According to Brett Phillips, La Puentes director of street services, there are currently 143 active clients who qualify as homeless in Alamosa. Among those 143, 30 people are living on the streets, 35 are living in a vehicle, 42 are living in a shelter and 36 are living in St. Benedict’s Encampment.

But there are also hundreds of households — individuals and families — that have lost their housing and are living with friends or family members, sometimes moving from one location to another while they wait for a housing opportunity to open.

Alamosa Housing Authority currently has more than 150 families waiting for housing and SLV Housing Coalition has 73.

That’s a total of about 225 families, which can range in size from a single individual to a family of six people or more.

And, according to Melgares, that waiting period is expected to be two to three years long.

Meanwhile, the ripple effect of multiple families being without their own home is making itself known. Lori Smith, principal of Alamosa Alternative School, says 25% of her students are “couch surfing” with four 18-year-olds who, due to different circumstances, have “struck out on their own” and without a home while trying to finish high school.

Although Smith could not divulge specifics, she says, “Their stories are heartbreaking.”

The city steps in

As a city, Alamosa is struggling with some significant issues, including a significant prevalence of substance abuse among some members of the community as well as people dealing with issues related to mental health.

One statistic to back that up can be found in date collected in 2020-2021. According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the drug overdose rate in Alamosa was three times the state average.

While a number of intervention strategies are being implemented, such as the co-responder program recently started by the Alamosa Police Department and the city’s involvement in the SLV Regional Opioid Steering Committee charged with determining the use of the settlement funds from the national court case against opioid manufacturers and distributors, the crucial component to developing a long-term approach relies upon stable housing for those who are in crisis.

“Studies have shown that access to housing is the number one driver for addressing homelessness,” Brooks says. “It’s impossible to help someone get regular treatment for mental health or substance use disorder if they are unhoused. If they have stable housing, then they stand a chance at being successful with the other issues.”

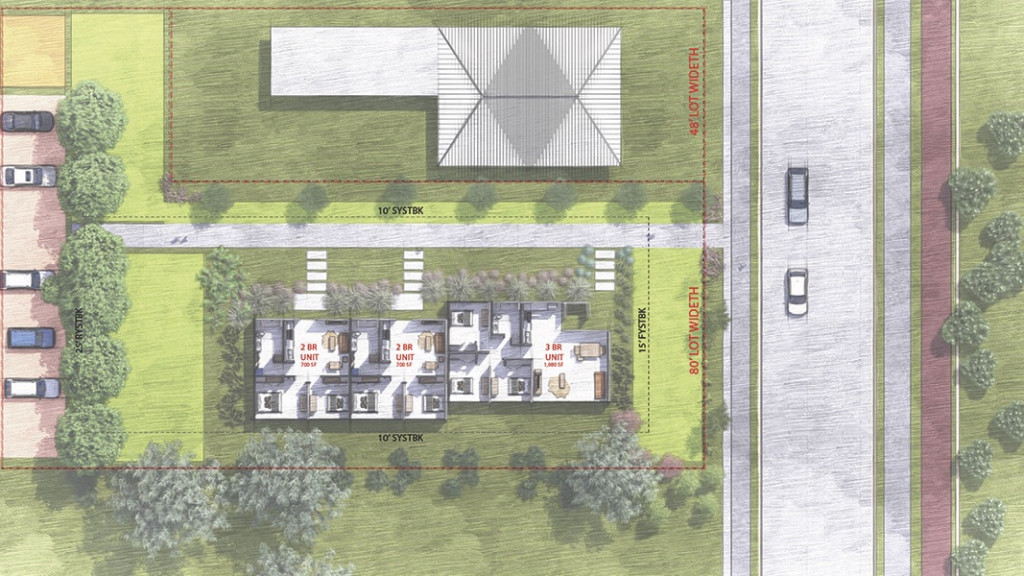

Toward that end, the city is partnering with several key organizations to address the housing shortage, including a project with CRHDC for 400-plus unit development that includes a variety of affordable housing units from single family to multi-family. Alamosa is also working with SLV Housing Coalition on converting the Boyd School into affordable housing and saving the Century Mobile Home Park.

They are also partnering with SLV Health on developing workforce housing geared toward healthcare, government, and education employees and, finally, in one of their most recent plans, working with SLV Housing Coalition on building and operating affordable housing on Airport Road. The housing will be near SLV Behavioral Health with a contract to provide wrap-around, case management services for individuals in that housing to increase success rates.

“Five years ago, the city was not involved in any of these types of discussions, but we're now fully involved and trying to move the needle,” Brooks says. “We’re trying to tackle these issues while balancing oftentimes competing values and motivations. It’s not easy or fast but the only alternative is doing nothing, and that’s not working anywhere.”